Executive Summary

Don’t let investment tax traps derail your retirement plans! Carson Johnson covers six tax traps that you should avoid in retirement. These tax traps include short-term vs. long-term gains, ignoring Required Minimum Distributions, Roth conversions, ignoring step-up in basis, failure to do a Qualified Charitable Distribution, and not understanding the benefits of a Donor-Advised Fund.

6 Investment Tax Traps in Retirement: Welcome to the Webinar (0:00)

Carson Johnson: Let me start with an introduction and what we’re talking about today and introduce myself and Kaden. So we’re both excited here to talk about the topic today, which is ‘6 Investment Tax Traps in Retirement.

Learn more about our Retirement Planning Services

For those that don’t know me, you haven’t met me yet, my name is Carson Johnson. I’m a Certified Financial Planner™, one of our lead advisors here at Peterson Wealth Advisors.

Also with me today is Kaden, he’s another one of our Certified Financial Planners™ and advisors here, and he’ll be helping monitor the chat and the Q&A. So if you have any questions, feel free to use the chat and Q&A feature. It’s located at the bottom of your Zoom. So if you hover over the bottom, it should give you an option to click to chat or Q&A to be able to ask any questions along the way.

A couple of housekeeping items. First of all, thank you all so much for giving us feedback on the last webinar. Many of you mentioned that we’ve been going over some of the same material over the past few webinars, and I promise that we will be getting a little more detail into specific topics.

You may notice today that there are a couple of topics that may have some overlap from last time, but the main focus of today’s webinars is to focus on the tax traps or common mistakes that we see with investments. And so that’s the focus of today’s webinar.

And so there might be some overlap but there is also some new material that we haven’t gone over yet and I think will be helpful for you all.

We figured today’s presentation will be about 30 minutes with a short Q&A afterward. So if we don’t get to your questions throughout the presentation, we’ll stay after for just a few minutes in case you want to ask your question.

And if it’s something more pertaining to your own unique situation, feel free to set up a consultation that’s completely free. Happy to go over your situation and see how we can help these principles apply to your situation.

So with all that said, oh, and then at the end also, there will be another survey, and thank you for the ideas that you shared with us on future topics. Please send those to us if you want us to talk about any other topics that you’re interested in.

So with that being said, let’s get started.

So here’s a little overview of what we’re covering today.

- We’ll go over short-term versus long-term capital gains and how you can manage that and the different applications of capital gains.

- Consequences of ignoring what’s called step up in basis, and I’ll talk about that. But essentially it’s an important principle as it pertains to inheritance.

- The impact of ignoring Required Minimum Distributions and the importance of having a plan for those.

- Roth conversions, considerations to think about to avoid converting too much or too little to make sure you’re maximizing the benefit of conversions.

- And then lastly, common charitable giving mistakes. Maybe not necessarily what the planning strategies are, but common mistakes that we see for those that are charitably inclined in retirement.

Capital Gains: When would they apply to me? (3:13)

So first, let’s talk about capital gains and when they would apply to you as a retiree. So first, what is a capital gain? A capital gain simply put, is when you sell a capital asset or an asset for more than what you originally paid for.

So for example, if you sold an investment property, that’s an example. There are some important and more unique rules when it’s an investment property, things like depreciation, and that makes it has a little more unique nuance to the sales and investment property. But, the sale of investment property does still qualify for capital gains.

Another example is the sale of an investment in a brokerage account. So for example, if you have a non-retirement account, you know, where you either got an inheritance or a sum of money that you decide to invest. And you can invest that in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, ETFs, a variety of different investments. And you sell those investments at a gain or for more than what you paid for, that would be an example of when capital gains would apply.

The other example would be the sale of a business. So oftentimes we run into retirees who are business owners and when they sell their business, some of it will be considered a capital gain because they purchased or put into the business a certain amount. It grew in value, they built up the business, now it’s worth more than what they paid for, and by selling it they also realize capital gains.

And there’s some unique nuances to that as well that we’re not going to be diving in for the webinar today, but it’s important to think through those aspects.

And then lastly, are mutual funds. Now I want to hit on this just a little bit deeper as it pertains to investment accounts and investment portfolios. You know mutual funds, they’re unique because they’re run by a mutual fund manager or somebody that’s in charge of that fund. And that fund will be investing in a variety of investments of stocks, bonds, options, things like that.

And what happens is occasionally if people either need money from their investment, from their mutual fund, they will ask to sell shares of their mutual fund and so the mutual fund manager has to free up some cash in order to get that cash to the investor. And so what happens occasionally is the mutual fund manager will have to sell investments within the mutual fund for a profit or for more than what they paid for. And so when those capital gains occur, the mutual fund manager doesn’t report those capital gains. He shares those or distributes that capital gains to all the investors or anybody that owns shares of that mutual fund.

So it’s important to know that mutual funds are notorious for this, especially at the end of the year, that mutual funds will issue out what’s called short-term capital gains, which we’ll dive into a little bit more detail, but just issue out these capital gains. And even if you don’t sell your shares of your investment, those capital gains may still be distributed to you that you may be required to report on your tax return.

So be cautious of that and how mutual funds can create extra tax consequences to you as an investor.

So now that we’ve gone over kind of a few examples of what is a capital gain, and in certain applications and how they can apply, let’s talk about the two main categories of capital gains, which is short-term and long-term.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Capital Gains (6:56)

What is a Short-Term Capital Gain?

So simply put, a short-term capital gain is when you purchase an asset and within 12 months you sell it for more than what you paid for it.

What is a Long-Term Capital Gain?

A long-term capital gain is when you purchase an asset and hold it for one year or more and then you sell it.

Rules of Short- and Long-Term Capital Gains

There’s a few important rules on how this works with these categories that you should be aware of.

Both must be Reported on Your Tax Return

First, both short-term and long-term capital gains must be reported on your tax return. Most taxpayers don’t have to worry about figuring out if it’s short-term or long-term because if you have an investment account, for example, you’re just issued a tax form.

Or if you have a CPA, a CPA can help you with that. If it’s more unique for like a business, for example, might be harder to have, you know, there might not be a tax for that unless there’s K-ones and things like that that you could get. But a CPA can help you but for the most part, taxpayers don’t have to worry about it. It’s already taken care of, just have to get the tax form and report it on your tax return.

You Don’t Pay Capital Gains Until You Sell that Investment

Rule number two, capital gains occur in the year that you sell an asset for a profit. So if you buy an investment and you hold it, you don’t have to pay capital gains until you sell that investment. And that occurs in the year that you sell that asset for a profit.

Each Kind of Capital Gain is Taxed Differently

And then third, short-term and long-term capital gains are taxed differently. So this is where we start to dive into the more planning parts of capital gains and we’ll talk about that next on what are the differences in short-term and long-term capital gains.

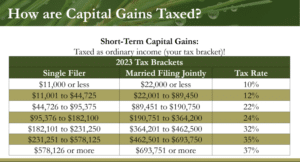

So, let’s dive in. With short-term capital gains, short-term capital gains are taxed as ordinary income. So in other words, what that means is it simply means that the capital gains are taxed at your tax rate.

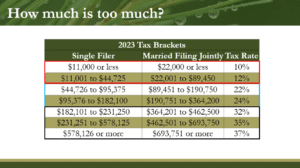

So I have listed on the slide the 2023 tax brackets for those that are single filers as well as those married filing jointly, and it shows you the breakdown of the tax bracket.

So for those that don’t understand or know how this works, depending on how much your combined income is, determines what tax bracket or tax rate that applies to.

So for example, if you’re combined income for a married filing jointly is between $89,000 and $190,000, that income is taxed at that 22% rate.

And so whatever rate that you’re, whatever your tax rate is depending on your level of income will determine how much your short-term capital gains are taxed at.

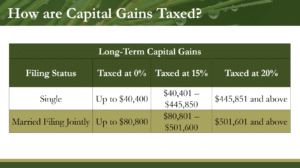

Now for many, as it pertains to long-term capital gains, long-term capital gains are taxed at either 0%, 15%, or 20%. And for many investors, those rates are a lot lower than the ordinary income tax rates.

Now, there’s exceptions of course for those that are maybe on the lower end of the income tax brackets, then capital gains could be higher. But for most retirees and taxpayers, they are at lower rates.

And so you can see with long-term capital gains, how it works is depending on your level of income, also determines your tax rate. So for a single filer who has income of less than $40,400, any capital gains are taxed at 0%. Now it’s important to keep in mind that capital gains adds on top of your other income. So let’s say the single filer has maybe $35,000 of income, but then maybe let’s say $40,000 of capital gains.

That $35,000 and the $40,000 capital gains adds on top of the $35,000 of other income that that filer may have. So really, their total combined income is going to be about $75,000 right? So then that would jump the capital gains tax rate at 15%.

So it’s important to keep in mind that your capital gains add on top of your ordinary income, and depending on your combined income determines what your long-term capital gains are taxed at.

For married filing jointly, for those that have income less than $80,800, capital gains are taxed at 0%. For those of income between $80,801 and $501,600, it’s taxed at 15%. And then those that have income above $501,601 capital gains are taxed at 20%.

So really to summarize it, short-term capital gains are taxed at your tax rate. Long-term capital gains are taxed at either 0%, 15%, or 20% depending on the level of income and what bracket that you are in.

Step Up of Basis – Inheritance (11:50)

Next, let’s talk about the step up in basis. And this particularly pertains to inheritance. We had a lot of questions regarding, you know, inheritance and how to handle inheritance in retirement. And so this was one of the common questions and planning strategies that we wanted to address today and to make sure that you’re using the effective use of the step up in basis.

So to simply explain what step up in basis is, it’s simply a way to adjust what the capital gains taxpayer will owe for selling a particular investment. So it’s very related to the capital gains discussion we just had.

When someone inherits a capital asset, things like stocks, mutual funds, bonds, real estate, investment properties, etc., the IRS will step up the cost basis or what you originally purchased those properties or assets for.

So for me, the purpose of the capital gains tax, the original cost that you had for any given investment is stepped up to the current value of when the asset was inherited. So let me give you an example to help solidify what I mean by that.

Let’s talk about Jack and James. Jack is James’s father and he’s a retiree. He owns Apple stock that he purchased back in 2010 for $20,000. He wants to give those Apple shares to his son James.

And so what he’s decided to do is rather than gifting the shares, he’s just going to sell his shares and give him the cash so that he can be able to do with the cash that he wants.

So Jack purchased the shares for $20,000. The sell price or the current value of those shares is $100,000, and Jack would realize that long-term capital gain of $80,000. And the tax rate on that, assuming a 15% tax capital gains rate on that capital gain, equals $12,000 of taxes that Jack would have to pay by selling Apple shares.

Now, let’s see how a step up in basis will work. So Jack purchased the Apple shares for $20,000. Jack passes away. James inherits the Apple stock at the current value of $100,000. If James decides to sell the Apple stock for $100,000, then James will then owe $0 in capital gains because James inherited that stock, and he received what’s called a step up in basis.

So instead of the $80,000 capital gain that Jack would have done if he sold the shares and just let James inherit that Apple stock, that original cost of $20,000, steps up to the current value of $100,000. So when James sells it, there’s no capital gains. It essentially wipes out the capital gain that the original or deceased owner had to the current market value.

And so it’s so important, this is probably one of the big misconceptions that retirees have and when they’re trying to distribute assets. Sometimes they’ll do that during their life and then they’ll think, hey, I’m just going to sell this and give it to my kids now.

It’s so important that you think about the tax implications when it comes to an inheritance because just this idea of letting your heirs inherit those assets and receiving that step up in basis, could save tens of thousands of dollars, by simply just being mindful and intentional about how you’re heirs receive those assets.

So, it’s such an important concept.

Now I want to just highlight a few takeaways about the step up in basis. Step up a basis can apply to stocks, bonds, mutual funds, real estate, and a lot more. Really, essentially any type of asset, capital asset. There are some exceptions that you have to be cautious of like things like jewelry, collectibles, that have different rules that apply to those.

But for the most part, a lot of the main assets and investment assets like these, a step up in basis does apply.

The step up in basis resets the cost like we’ve talked about. Spouses who inherit property from a deceased spouse may only qualify for half of the step up in basis. So, you know, coming back to you know, Jack and James. Let’s say Jack had a wife, and his wife inherited some of the Apple stock. Instead of receiving the full step up in basis up to $100,000, they may only receive up to $40,000 of that step up in basis which helps reduce the capital gains, but it doesn’t eliminate the capital gains entirely.

Now, there is one exception for this half step up in basis, which is for those that live in community property states. Those are states such as California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin. If you live in any of those states, your surviving spouse may qualify for the full step up in basis. And so just be aware of that when you’re planning how you want to distribute your assets.

And then lastly, just have a plan on how you’re going to distribute your assets. You know estate planning is such an important aspect of a retirement plan. It’s not just about, you know, making sure somebody’s there to handle your estate or to make certain medical decisions. It’s also about how you want your legacy to be passed on to your future heirs.

The Impact of Ignoring Required Minimum Distributions (17:38)

Okay, next let’s talk about the impact of not having a plan for Required Minimum Distributions. Now some of you that are aware of this, Required Minimum Distributions is a law, that for those that have an IRA or 401k, are required to pull out a certain amount of money once you reach a certain age.

And we’ll talk about that in just a moment. Now in some cases, many of you may be living off of your IRA or 401k income and may satisfy that required amount each and every year. And so this may not be as big of an issue for you.

However, I’ve seen time and time again where retirees will have Social Security income, a pension, maybe rental income, or income from a business. And so they may not be pulling out the full amount from their IRA to satisfy the Required Minimum Distribution. What happens is that IRA, your investment account just continues to get bigger and bigger and bigger which creates a bigger Required Minimum Distribution later in retirement.

So I want to go over a few mistakes and things to think about when what happens if you ignore those Required Minimum Distributions.

As a reminder, since the passing of The SECURE Act 2.0 in December last year, one of the biggest changes was the change to the RMD age which will affect nearly every retiree. So the changes that were made is that the RMD will push back starting this year.

And for future years, I made a summary on this slide here of those changes. So for those that were born in 1950 or earlier, your RMD will continue to go on as normal. For those that were born in 1951 to 1959, your Required Minimum Distribution will be age 70, to start age 73. And those that were born in 1960 or later, your Required Minimum Distribution will start at age 75.

Now there are a couple important points to remember and to clarify. Those that are turning 72 in 2023 will not be required to take an RMD until next year. Also starting in 2033, that’s when RMDs will begin at age 75. So that’s why those born in 1960 or later will start at age 75.

So first, let’s look at mistake number one for ignoring RMDs. And first, it’s the penalties involved. So if an IRA account owner fails to withdraw the RMD, they may be subject to a 50% penalty tax. Now with The SECURE Act 2.0, there was also a change to this. So if you fail to pull out the required amount and you realize that and you say, oh I want to go ahead and fix that. And you fix that within that timely matter within two years, the penalty drops to either 25% or even 10% if you do it even sooner than that.

So you can work with the CPA or tax professional to help make sure that it’s reported correctly or corrected. But that’s something that’s so important. Do not miss the Required Minimum Distributions because there’s pretty hefty penalties.

Mistake number two, ignoring the impact of RMDs. So I want to share this PDF with you, let’s see if technology will work for us here. Okay, perfect.

So let’s focus here on this table on the left. What I’ve shown is an example of, let’s say you’re not necessarily needing as much investment income. You’ve got your income taken care of from Social Security, pensions, or other sources. And if you were to just let your IRA retirement account continue to grow, to show you the impact that it will have later on and retirement.

So in this case, if you’re a 60-year-old retiree, you have a million-dollar IRA, or retirement account, and assuming just a 4% growth rate by the time this retiree turns age 73, at Required Minimum Distributions, the RMD will be about $60,769. Pretty crazy how big that RMD can be.

Now I want to point out a couple of other things. If we continue to look at the Required Minimum Distribution, and assuming that we take out the full RMD each year, you’ll notice that the RMD still continues to get bigger.

Right, even though you’re still taking out the $60,000 about each year, you know, it still continues to get bigger. And the reason for that is because, how the IRS calculates your RMD is, it’s based on one how big your account balance is.

And two, if it’s based on your age. And so as you get older and as your account gets bigger, the bigger your RMD will be. And so that you can see how this could be a problem later in retirement, more taxes that you might have to pay, and we’ll talk about some of the strategies to avoid that.

But I want to show you this other chart here, which shows you the tax brackets. But let’s say this retiree has taxable income of about $130,000 from other sources things, like Social Security, pensions, or income from the business, rentals, etc.

By adding this $60,000 worth of RMDs, that ends up bumping this taxpayer from the 22% bracket to the 24% bracket. And so just letting that RMD ride and not having a plan for it could significantly increase the amount of taxes that you pay. And so being mindful how you do that whether it’s through Roth conversions or drawing a little bit each year and then putting that money into, even if you’re not spending it, putting into a non-retirement account to keep it invested, you know are some examples and ways you can manage your RMD.

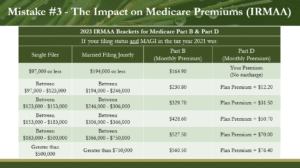

So, now let’s move on to mistake number three, which is the impact on Medicare premiums. So if you think back on the previous side when I showed you how the RMD can possibly bump you up into a higher tax bracket, there’s also RMDs can also impact the amount of your Medicare premiums.

So the table that you see on the slide shows a summary of how your Medicare premiums are priced at, and they’re based off of your income.

How this works is Medicare looks at your income two years prior. And if your income falls within one of these categories, it will determine what your monthly premium is. So, for example, let’s say you’re married filing jointly and your combined income, or to be more specific, you’re modified adjusted gross income falls between $194,000 and $246,000. Your Medicare premium will go up to $230.80 per person, plus your Medicare Part D premium, which is your prescription drug coverage, will be an extra $12.20.

So the base Medicare cost is $164.90, but you can see depending on your income, it could increase by the amount of your combined income that you have. So, you know, if you have your income taken care of and all of a sudden you have this big Required Minimum Distribution, not only could it jump you up into a higher tax bracket, but also a higher IRMAA, or higher Medicare premium bracket, which would increase the cost for you on a monthly basis for your Medicare.

And so, such an important thing, you can see that especially if you have a bit, excuse me, let me go back here, a big event. If you’re selling an investment property later down the road or sell the business, this could really increase your Medicare premiums, so important to be aware of that.

Now there are some exceptions to, you know, if you have like a one-time event where if you’re like, I sold this property, or I’m just retiring I’m not going to have the same level of income that I am going to have going forward. There are ways where you can file a form with Medicare and it’s kind of a forgive me this one-time kind of form where you can ask for forgiveness for this one and be granted an exception.

So if you have questions about how to report that form, we can send you an email, send us an email, we can explain that process to you so that you can avoid having higher Medicare premiums going forward if it’s a one-time event. They kind of, IRS bases it off as a lifetime event, lifetime changing event. So, good.

Roth Conversions: Converting too much or too little? (26:31)

Next, let’s move on to Roth conversions. Now in our last webinar, Alek and I talked about what Roth conversions are, but we didn’t dive into great detail on how much Roth conversions you should do and the impact of converting too much or too little.

So I want to focus on that here today. But just really briefly, let me just explain what the Roth conversion is for those that are just new and jumping on to this. A Roth conversion simply means that it allows you to take money from a pre-tax account like an IRA or 401k and convert it to an after-tax account, which is a Roth IRA or Roth 401k.

By doing this Roth conversion, you’re essentially paying taxes on the amount that you’re converting at your current tax rate. And so, the big consideration of when to do a Roth conversion is to ask yourself, when do I want to pay my taxes? Does it make sense to pay taxes today based on current tax rates or will my tax rate be lower in the future? Maybe waiting just to pull that money out of your regular IRA rather than converting and paying taxes on it today.

So, I want to illustrate this by showing you again the tax brackets. So as we saw the impact of the RMDs, the Required Minimum Distributions, and the fact that we are in fairly low, tax rates today, any amount that you choose to convert becomes taxable to you, like I mentioned. And it’s taxed with you in the year that the conversion is performed.

So it is very uncommon to convert an entire account because what happens if you convert an entire account, especially if it’s a large account, it’ll likely push you up into a higher tax bracket. Every dollar you convert will add to your combined income.

And so if you convert, let’s say a million dollars, or even $600,000, $700,000 of Roth conversions, that will bump you up to the highest tax bracket and you’ll pay close to about 40% in taxes.

Generally, the advice we give to clients is to convert enough to get the future benefits of a Roth conversion, but not too much that it pushes you up into the next tax bracket. So for those that are still wondering if a Roth conversion is right for you, I’ve highlighted kind of the different brackets into groups.

You can see the first tax brackets are at 10% and 12%. And then there’s a pretty big gap or jump to the next tax bracket of 22%. So for those that are maybe a lower income tax situation, doing conversions at the 10% and 12% are at the lowest rates that we’ve had in a very, very long time.

And so doing a Roth conversion may make sense, especially if that Required Minimum Distribution is going to jump you up into a higher tax bracket. So you should definitely consider doing a Roth conversion if you’re in those lower tax brackets.

For those that are the middle-income earners, those that are in the 22% and 24% tax bracket, you can see that there’s a very little difference between the two. And so if your tax rate is going to be the same as it is today versus what it will be in the future, a Roth conversion may not be as convincing from a financial standpoint or mathematically, right?

Because if you’re going to pay the same rate today on the conversion as you will in the future, you might as well just leave it in the IRA.

However, there are some other non-financial aspects that you may still want to do the conversion. Even if the tax rates are going to be the same things like, you know, your heirs. If this money is going to be passed on to your heirs, one of the big changes that happened with The SECURE Act 2.0 is any heirs that receive an IRA may be required to withdraw or distribute all the money in an IRA within a 10-year time period.

And so you can see how that could have a big impact to heirs, your kids or nephews, nieces, the people that will be inheriting your IRAs because that could jump them up into higher tax brackets and essentially lose out the benefit of a Roth conversion.

For those that are in the higher tax brackets, you know the 32%, 35%, 37%, then a Roth conversion may not again be as convincing. That’s where it will be important for higher income earners to focus on pre-tax accounts and contributing to an IRA or 401K because that reduces the amount of taxable income that shows up on your taxes. Doing Qualified Charitable Distributions, which we’ll talk about later, which allows you to pull money out of your accounts tax-free may be more advantageous than a Roth conversion.

So I like to break it up into these different groups to give you an idea of when you might want to consider doing a conversion and also help give you the boundaries of when to know when too much when you do a conversion, is too much or not enough to really get the benefit out of it.

All right, so let’s talk about some other non-financial considerations. First, is where you will live in retirement. So even if you expect your federal tax rate to stay the same for those middle-income earners for example, where your tax rate may be the same. The difference that some states may partially or entirely tax that retirement income as well. And so from a state income tax perspective, and there may be a reason to do some Roth conversions.

If your future state of residence has a higher state income tax than that of your current one, it definitely makes sense to at least convert some of your assets to a Roth IRA before you move in the state that you have. Let’s say your current state doesn’t have state income tax, but you’re moving to a state that does have state income tax. That might make sense to do some conversions there. And as we keep in mind the other factors like Medicare premiums, tax rates, and things like that.

Another consideration is Required Minimum Distributions. We talked about this, if you ignore it and don’t have a plan for it, then that could create a bigger problem later in retirement. So it may make sense to do Roth conversions from now until you’re Required Minimum Distribution age to help reduce the impact that might have later down the road.

Consider tax rates in Medicare premiums. So just like the Required Minimum Distribution, Roth conversions for every dollar you convert, that adds additional income that you have to report. So that may also impact what your Medicare premiums are. So be careful, it’s a common mistake that we see with retirees as they end up, you know, they get carried away and saying, oh I want to convert all my IRAs.

I think that our tax rates are going to go up and although that may be the case, they may not realize the other costs that are going to happen with taxes and Medicare premiums and things like that.

Lastly, is leaving money to others, and I touched about this just a few minutes ago. But if you’re planning to leave a retirement savings to heirs, consider how it may affect their taxes over many generations.

And like I mentioned, where there’s new rules in play with The SECURE Act 2.0, and that they may be required to pull out all that money after 10 years. That could be a great reason especially if you’re in a lower tax rate in retirement to do some Roth conversions so that your heirs can receive more of your inheritance to them, then if they didn’t, if you ignored it.

Common Qualified Charitable Distribution Mistakes (34:29)

So, lastly is common Qualified Charitable Distribution and charitable giving mistakes. So with many retirees, especially those that we work with, are charitably inclined and plan to give in retirement.

A Qualified Charitable Distribution is a provision and tax code that allows you to withdraw money from your IRA tax-free as long as it goes directly to a qualified charity.

There’s huge tax savings that we talked about in the last webinar. If you think about it, you put money into an IRA or 401k and you didn’t have to pay tax on it. You didn’t have to pay tax on the compound interest or growth over maybe 20 or 30 years of your working career.

And then when you do this strategy, allows you to pull money out of that account now tax-free as long as it goes to charity. So you’re essentially getting triple tax savings by doing this strategy. I would recommend any retiree that is inclined to do and have charitable intentions in retirement should consider this. And we’ll talk about some of the rules and mistakes that we see and how to correctly process these in retirement.

So some of the four benefits and how it can benefit you. It can potentially reduce the taxes on your Social Security benefit. It will reduce the overall amount of income that is taxed and that may also impact your Medicare premiums like we talked about.

It’ll enable you to get a tax benefit by making the charitable contribution. And then Qualified Charitable Distributions count towards satisfying the Required Minimum Distributions later down the road.

So here are some important rules to be aware of. They are only available to people older than age 70 and a half. And to give this a little bit more specific, the IRS doesn’t allow you to do it a day earlier. So even if you’re in the same tax year as you’re 70 and a half birthday, if you do a QCD before your 70 and a half birthday exactly, the IRS could come back and say that that is ineligible. So you have to wait till the to the exact day of your 70 and a half birthday.

Second, they are only available from IRA accounts. Withdrawals from 401ks are not eligible for QCDs. So I’ve seen this time and time again as well, retires will try to withdraw money from their 401K. They’ll receive the check or cash and then send the cash directly to the charity. That is not eligible for QCD. And that could, the IRS could come back and deny that.

A QCD must be a direct transfer from an IRA to a qualified charity. And one example that I’ll give you to illustrate this point. I had a client of mine who actually had the ability to get a checkbook for their IRA. It’s pretty common for a lot of the broker-dealers and custodians like Fidelity Investments, Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade. They typically have that as an option or a feature. And this client of mine was writing checks to the church directly, and so even though he was writing the check and the money was going to the charity. Essentially, that money was coming directly from him, not from the IRA account.

So you have to make sure when you’re working with your custodian, filling out the paperwork, that it is going directly from Charles Schwab or Fidelity Investments, wherever you’re investment accounts are held to the charity. Writing a check from your IRA does not count, is not a Qualified Charitable Distribution.

Then lastly, a QCD does not count as an itemized deduction. This is so important, or let me just reiterate what I kind of first started and explained the QCDs. QCDs simply allows you to pull money out of an IRA tax-free when normally it would have been taxable to you. It’s not a tax deduction, it’s simply not, you know, you’re just avoiding having to pay tax on that money that you pull out.

So a common mistake that we see some people say, you know, I’m going to exclude this from my income. But also, I’m going to count it as an itemized deduction. If you do that, then the IRS could come back and audit you for that and that could be a big mistake there.

So, when it comes to QCDs, one of the most important aspects is making sure you get the reporting right. So I’ve taken a screenshot of a sample tax return which shows you how it should be reported.

So for example, let’s say you’re retiring, you withdrew a total of $40,000 out of your IRA. But only $25,000 of it was a QCD or Qualified Charitable Distribution.

Then what you show on the tax return is you show the full amount, in box 4a, $40,000, but the taxable amount is the difference between the total and the charitable donations that you’ve made. And so that remaining amount, this $15,000, is the only amount that you’re taxed on because the difference was your charitable distributions.

You have to be, this is how you have to do it and actually write it in on your tax return. Some tax software may account for that. But you have to be very careful with tax software that it is reporting correctly. So if you have questions about making sure that it’s processed correctly, I’ve included this link here, and Everett will make sure that when he sends an email tomorrow that this link is included to make sure that you’re reporting it correctly.

Improper Use of a Donor-Advised Fund (40:04)

Okay, lastly I’ll just wrap this up here, is the improper use of a Donor-Advised Fund. So a Donor-Advised Fund simply is a tool and not an investment. It allows you to be able to make a large contribution to a Donor-Advised Fund and to get a tax deduction and then it allows you to distribute that money to your charities over time.

So for example, if you don’t need cash or even better, securities like stocks or bonds or any other type of investment to the Donor-Advised Fund, whatever year you do that you get a tax deduction. And then that money sits in that Donor-Advised Fund until you’re ready to distribute it to the charity.

So, there are some practical applications of how this could work. A Donor-Advised Fund is very helpful when you’re trying to get a larger deduction, warrant deduction for charitable purposes, or tax purposes. And it gives you more flexibility on how you can distribute that to a charity.

A Donor-Advised Fund helps you get a tax deduction when it’s needed most. Especially if you’re selling a business or property and you have a larger-than-normal income year. And then you can create a charitable fund for a legacy for your future family.

The ways that it can turn into improper use for a Donor-Advised Fund is when you decide to invest that money within the Donor-Advised Fund and you invest it improperly. A lot of times Donor-Advised Funds have a select mutual fund that you can invest in, and some people go maybe a little overboard and try to invest it too aggressively. And then if the market drops on any given day the value of that money could go down. So be cautious of what you’re investing in within your Donor-Advised Fund.

If you contribute too much to a Donor-Advised Fund, you may have left over. And especially if you’re eligible for Qualified Charitable Distributions, this may reduce the benefit that you’re getting from QCDs.

Because if you continue to just grant money or gift money to the charity from your Donor-Advised Fund and not take advantage of your Qualified Charitable Distributions, then you may still have big Required Minimum Distributions that you have to deal with.

So be cautious on how much you contribute to a Donor-Advised Fund.

And then lastly, if you’re planning on gifting the entire contribution to the charity, there’s no reason to set up a Donor-Advised Fund. The purpose is to make a large contribution, have that money sit in the account, and gift it over time gradually. But if you’re planning on just gifting the whole amount, you might as well just gift it directly in the same tax year and avoid going through the headache of setting up another account and worrying about how it’s invested.

Key Insights (42:45)

So I know that’s a lot of information. Let me just summarize the main key insights of what we talked about today. So first is capital gains are taxed at different rates and it’s important how you manage those properly and be aware of how long you hold those assets for.

Second, retirees should have a plan that addresses the impact of Required Minimum Distributions.

Third, carefully consider how the step up in basis can reduce the amount of taxes paid from one generation to the next.

Fourth, a Roth conversion strategy should consider all aspects of your retirement plan. It should not just be made in a vacuum. It should be carefully considered.

And then lastly, be wise on how you do your charitable giving strategies. Just those simple mistakes can eliminate the benefits that you get from those strategies.

Question and Answer (43:36)

Thank you all for attending today. I’m sorry I went a little bit over but we will stay on for the next five minutes to answer any questions. I see there’s a few there, and again, feel free to take that survey. Please rate us there and give us some more ideas of what we can talk about in future webinars.

So I’ll turn the time over here to Kaden, and Kaden are there any questions that you thought were great that we can answer with everybody?

Kaden Waters: Yeah, I saved a couple and then it looks like we had one that came in late. We’ll just have you answer a couple of these. The first two were about the Medicare IRMAA that you covered there.

Question: Are Medicare premiums calculated based on both spouses’ incomes or individual?

Carson Johnson: Yeah, great question. It depends on how you file your taxes. But if you’re married filing jointly, for example, the Medicare premiums since you’re filing jointly will impact both spouses. And so, you know, let’s say you jump up into the higher tax bracket, the Medicare bracket. Let’s say instead of $164.90, it jumps you up to $230. Then both of your Medicare premiums will be $230. So yeah, it’s a great question. It will impact both spouses if you’re married filing jointly.

Question: Do Medicare premium prices lock? Or are there price increases?

Carson Johnson: Oh great question. Yeah, so what happens is the IRS always looks at your income from two years prior. So it doesn’t lock it in, so let’s say you had a high-income year two years ago, but then so in 20, let’s say 2021, but then in 2022 your income went back down to normal levels.

Then you’re your Medicare premiums would drop back to the normal levels as you normally had it, so it doesn’t lock you in.

Question: Do you evaluate Roth conversions that are appropriate for an individual?

Carson Johnson: Absolutely, yep, that’s definitely part of our process when we’re working with people. We will look at all those non-financial aspects that I talked about, but also, you know, kind of doing that analysis looking at their last year’s tax return to see what tax bracket they’re in and just talk through that with them. See if it makes sense and if their Required Minimum Distribution will jump them up into higher tax brackets and things like that.

Question: If you do QCDs, will you likely take the standard deduction?

Carson Johnson: Yep, that’s exactly right. So because the IRS allows you to pull that money out tax-free, you can essentially double dip and also count it as an itemized deduction. So yeah, it’s just simply, it’s not a tax deduction. You just don’t get to be taxed on that income that you pull out.

Question: With capital gains, I understand them being capital gains are taxed at a capital gains rate. But the rest of ordinary income without capital gains is still taxed at your ordinary income tax rate without figuring in your capital gains, correct?

Kaden Waters: And yeah, that is right. So it’s just the portion of your capital gains that exceed that threshold will be taxed at the higher capital gain rate.

Carson Johnson: That’s perfect, and then I did see one other one, I’ll just answer this.

Question: Can you roll over 401K into an IRA and then make a QCD from the IRA?

Carson Johnson: The answer is yes. Doing that rollover is not taxable. So that’s a great way to roll it over to the IRA so you can be able to do that strategy.

Well good, well, if you have any other questions, feel free to send me an email or to our firm. Happy again to dive into more of your situation if you have more unique questions to you. But anything pertaining to what we talked about today, happy to help answer those questions for you and hope you find this helpful for you.

Kaden Waters: Yep, have a great rest of your day.

Carson Johnson: Thanks.

Carson Johnson is a Certified Financial Planner™ professional at Peterson Wealth Advisors. Carson is also a National Social Security Advisor certificate holder, a Chartered Retirement Planning Counselor™, and holds a bachelor’s degree in Personal Financial Planning and a minor in Finance.